APCs at Long Tan

August 18, 1966, was supposed to be fun for the troops at the 1st Australian Task Force Base at Nui Dat.

A concert had been organized, and entertainers Little Pattie and Col Joye were flown into the base to provide a much-needed distraction from the war.

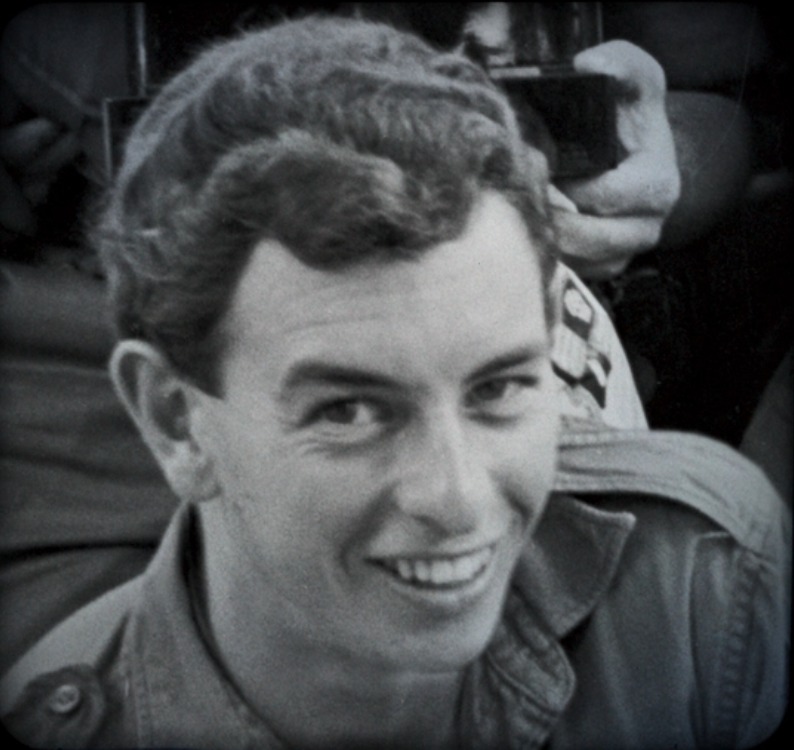

Twenty-one-year-old 2Lt Ian Savage was caught up with the festivities, being selected to collect the entertainers from the helipad in his APC.

The concert started, but the increasing tempo of outgoing artillery made it obvious that something was very wrong.

To the east of the Task Force, D Coy 6RAR had commenced a battle in a rubber plantation near the village of Xa Long Tan, which would later mark one of the most significant engagements by Australians in the Vietnam War.

Battle Prep

At about 4.50pm 3 Tp commander Lt Adrian Roberts was summoned for orders at 6RAR’s lines.

He was to lead a depleted troop of ten APCs, loaded with infantrymen from A Coy 6RAR, to the Long Tan rubber plantation, where the 108 soldiers of D Coy 6RAR were locked in combat with a massive force of up to 2500 enemy.

A Coy had just returned from the field, but they were rapidly being replenished to return to assist D Coy.

1986 Detailed Presentation by Lt Adrian Roberts about APCs he led into the Battle of Long Tan:

Finally, the time came to move out, but before the APCs had left the base the CO of 6RAR instructed Roberts to send back two carriers to fetch the battalion headquarters element.

So Savage’s APC, 30 Bravo, and Cpl Jock Fotrill’s 33 Alpha returned to collect them. Savage remembers the occasion well.

“It came over the air that Adrian was to dispatch vehicles to collect Lt-Col Colin Townsend, because elements of B Coy, 6RAR, who were on foot in the scrub, were also trying to get back to D Coy,” he said.

“We went back flat-out through the task force base, and he was ready to go with his radio operator and his HQ Group.”

The headquarters was loaded, and they raced to join the rest of the troop.

Into Battle

“I had two radio nets; one was the net to squadron headquarters, back at Nui Dat, and the other was our own troop radio net.

“Lt-Col Townsend, in the back of my vehicle, was on the infantry net, and he was speaking directly to Maj Harry Smith (OC D Coy, 6RAR).

“So he was standing behind me with his head out of the cargo hatch, relaying messages to me, and telling me what he wanted Adrian to do.”

The two APCs raced to the crossing point over the Suoi Da Bang stream.

“They [the rest of the troop] had crossed the Suoi Da Bang while we were trying to catch up and had left a vehicle there for security.

“Adrian was told to wait for Lt-Col Townsend, but he made the decision to push on because he felt that he should get there ASAP.

“He kept going and we got to the Suoi Da Bang, and the security vehicle crossed — it was pretty tough crossing that creek, it was swollen, and the vehicle really had to work hard to get across.

“We just didn’t stop, I always remember my driver, Geoff Newman, just leant forward and pushed out the trim-vane and just went flat-out into the water.

“When we got to the other side, Lt-Col Townsend tapped me on the shoulder and said ‘D Coy is now under heavy attack, tell Adrian to get in there and get to them as quickly as they can’.

“I relayed that message to Adrian, but it was then they struck the enemy.” Up ahead the seven APCs under Robert’s control had come across about 100 enemy moving east to west.

At first, it was difficult to identify the soldiers, as their rain-soaked uniforms and bush hats made them look like Australians.

The enemy was also surprised at the appearance of the APCs.

“The rain was very, very heavy, it was a typical tropical torrential downpour, and that’s what muffled our engines and confused the elements of D445 [Viet Cong local-force battalion] that were sent around to the south of D Coy.

“They didn’t expect anybody to be coming up from the south, so they were moving very casually – they had their weapons over their shoulders, they were moving quickly, not ready for battle. “Apparently they were going around to block off D Coy’s retreat towards the Task Force base.

“Cpl Gross saw them first, I remember his radio conversation, he called ‘enemy in front, enemy in front’.

“Adrian said ‘hold your fire, they could be D Coy’, because we didn’t know exactly where they were.” But the spell was quickly broken, and a fierce firefight erupted.

The enemy fell back, and the formation continued towards the falling artillery that hopefully marked the area near D Coy’s position, but again the APC troop came across another enemy Coy of about 100 men.

On the right-hand edge of the troop, a shoulder-mounted 57mm medium recoilless rifle team engaged the carrier of Cpl John Carter.

The team fired two rounds, impacting in nearby rubber trees and destroying both radio antennas on top of the vehicle. Carter tried to return fire with his 50-cal but it jammed.

The enemy team was reloading when Carter told his driver to stop the vehicle and hand him his Owen gun.

In full view of the enemy, Carter shot and killed the team as they fired another round.

The driver was dazed by the concussion of the exploding round, but that didn’t stop him from throwing magazines up to Carter, who went on to kill another five enemy soldiers.

Meanwhile, the left flank was also receiving heavy fire from the enemy.

The left flank contained APCs from 2 Tp, which were newer than those of 1 Tp and lacked gun shields.

During the fight, the commander of the vehicle on the left flank, Cpl Peter Clements, was mortally wounded in the chest by enemy machinegun fire while manning his .50 cal.

Roberts ordered his Tp Sgt, Sgt Noel Lowes who was in the back of Robert’s vehicle, to dash across the open ground to take charge of the vehicle. This he did, nearly being shot in the process by A Coy troops in the back of Clements’s APC who thought he was the enemy.

Lowes called in that Clements was badly wounded, so Roberts made the decision to send the vehicle back to Nui Dat.

All this took time, and the section on the right flank, not grasping the full extent of the situation on the left flank because of radio problems, had moved on and continued to advance through the artillery and discovered the D Coy position.

They wheeled around the cheering survivors but then realised the rest of the troop was still in contact, so they headed back through the artillery to rejoin the troop and guide them back in.

By this stage, Savage’s group had caught up with Roberts, and together the APCs plunged into the artillery towards D Coy.

Meanwhile, Lowes was making the dash back to the task force to try to save Clements.

He was evacuated to the 36 Evac Hospital at Vung Tau, but he died of his wounds nine days later.

Arrival at D Company Position

“We pushed up parallel to the north track, then spun around onto the track that led east-west, using it as a pivot point,” Savage says.

“We went past D Coy to the south of their position and we started to take fire from our left and from our front.”

The APCs moved forward at a walking pace, forcing the enemy back through the volume of fire that came from the .50 cals and the troops from A Coy who fired from the open cargo hatches.

But it was not a one-way battle and the enemy fought back ferociously. “That was an eerie feeling too, I didn’t know you can see tracer coming towards you, and luckily the enemy were firing high – if you don’t have lot of practice you tend to shoot high.

“The bullets were going over our heads, which was quite strange, you see this slow-moving tracer and you feel you can almost dodge it.

“We returned to D Coy and stopped in a line facing east with A Coy on the ground between the vehicles, and waited for the assault.

“We switched off our engines and waited. I felt really low when we broke through to D Coy because there were dead soldiers lying there, and we didn’t know then what the actual battle result had been.

“When we switched our engines off and we were waiting to see if these bastards were going to attack us or not, could feel the fear.

“I was wondering if mortars would fall on us. We waited there for a while, but nothing came – there was some sniper fire, but that was it.

“It was decided that there wasn’t going to be another attack so our vehicles were placed in a hollow square formation around D Coy and the CO called an O Group, which Adrian and attended.

“I saw WO2 Jack Kirby (CSM of D Coy) shining his torch around in the dark trying to organize the wounded and bring in the dead, and I remember people saying ‘for Christ’s sake, turn that light off, you’ll get yourself shot’, but he kept on.

“He had incredible bravery, running around, shouting orders and looking after his soldiers.

To the Night Harbour

“Colonel Townsend made a decision that we weren’t going to stay there all night.

“He said ‘we are going to push to the west’, and he picked a spot on the map just outside of the rubber to take up a defensive position for the night and evacuate the wounded, because we couldn’t call the choppers in through the trees.

“We loaded on D Coy, and the half-dozen dead they had were loaded into my vehicle, which had about six to seven inches of water in the cargo compartment from the rain coming in through the cargo hatch.

“Once all were loaded, Adrian said my first order will be to turn your engines on, the second will be lights on and go’.

“That’s an old tankie trick – if you start all your engines together, nobody knows how many vehicles there are.

“Then we turned our lights on together – which was the only time we did turn our lights on during the battle – and we went flat-out back into the rubber, following the narrow gap between the rows of trees to the clearing.

“The distance between the rows of rubber trees was only just wide enough for an APC to fit through, so it was a scary ride at night.

“We then came into the clearing on the other side and formed a hollow square.”

Helicopters came to collect the wounded and dead and they were quickly loaded, but moving the dead was another matter.

“When they called for the dead to be taken from my vehicle, no one wanted to touch them. Kirby had to tell people to take them out. When they took them out, the inside of my vehicle was awash with water that was now stained red. “My driver and I had to sit in that through the night.

We just stood to all night, sitting with our boots in this water. I can talk about it now, but for a long time, I couldn’t.

11 Platoon’s Final Stand

The following morning the APCs headed off to the 11 Pl position.

11 Pl had been the first to contact the enemy and had suffered many soldiers killed and wounded.

The platoon had to withdraw the previous afternoon towards the company position to avoid being overrun, and the dead had been left behind and some soldiers were missing.

“We moved back in at a walking pace, with D Coy just in front of our APCs. “Before we got there we came across the two wounded guys who couldn’t get back to the D Coy base.

“They managed to survive the night, and we collected them and moved on. We pushed through the rubber to find 11 Pl. “… we arrived at 11 Pl’s position, and Maj Harry Smith (OC D Coy 6RAR) decided we would use it as our operational base and work out from there.”

“My troop commander said over the air ‘switch off your engines’. “There was a really eerie feeling that I’ll never forget because a lot of 11 Pl were lying in their firing positions.

“The ground was very flat, and a lot of them were shot in the head or the chest, and some of them looked like they were still alive.

“Everyone went really quiet when they saw this scene.

“I always remember the platoon radio operator had been killed, and he had the radio on his back in a harness.

“He had been shot in the chest and had knocked him back and he was still sitting up, looking down as if he was asleep. “The squelch on his radio was off, and you could hear the eerie hiss of static going right through the rubber.

“It was a really horrible sight.

“It’s a terrible thing, but when you see the enemy dead it doesn’t seem to matter so much because they were, you know, shooting at us, and they’re wearing foreign uniforms and weapons, and they look different, of course.

“But when you see your own soldiers dead, that’s when it really, really affects you. Seeing a person with the same GP boots on, seeing the same jungle greens on, it brought the realization that ‘there, but for the grace of God, go I’.

Postscript

Ian Savage remained in the Army until 1970, retiring as a Captain.

He found it difficult to deal with the memories of Long Tan, but relief came years later following the release of a book on the battle.

“The thing that helped me a lot was when Lex McAulay wrote the book The Battle of Long Tan in 1986.

“When I read the book and saw how it all fitted together, I felt I could finally talk about it.”

Facebook Comments